Minimally Disruptive Posterior Cervical Fusion with DTRAX Cervical Cage for Single Level Radiculopathy - Results in 10 Patients at 1-Year

Bruce M. McCormack, Edward Eyster , John Chiu and Kris Siemionow

Bruce M. McCormack1*, Edward E1, John C2, Siemionow K3

1Clinical Faculty, University of California San Francisco, 2320 Sutter Street, Suite 202, San Francisco, California 94143, USA

2Spinal Neurosurgery, California Spine Institute, 1001 Newbury Road, Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA

3Spine Surgery, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1801 West Taylor Street, Suite 2-A, Chicago, Illinois 60612, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Bruce M. McCormack

Clinical Faculty, University of California San Francisco, 2320 Sutter Street, Suite 202, San Francisco, California 94143 USA

Tel: 415.923.9222

Fax: 415.923.9255

E-mail: bruce@neurospine.org

Received date: Sept 29, 2015; Accepted date: Jan 18, 2016; Published date: Jan 20, 2016

Copyright: © 2016 McCormack BM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Objective: The authors present one-year clinical and radiographic outcomes of 10 patients with single level cervical radiculopathy due to spondylosis and stenosis treated with a minimally disruptive instrumented fusion procedure employing bilateral posterior cervical cages.

Keywords

Cervical radiculopathy; Cervical spondylosis; DTRAX cervical cage; Minimally disruptive; Posterior cervical surgery

Abbreviations

NDI: Neck Disability Index; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; AE: Adverse event; SAE: Serious Adverse Event

Highlights

One-year retrospective study of 10 patients treated with DTRAX Cervical Cage. Five patients were treated at C5-6, four at C6-7, and one at C4-5. All patients had successful radiographic fusion defined as 1.5 mm or less change in distance between adjacent spinous processes at treated level on lateral flexion/extension radiographs. Bridging bone on CT was present in 9 with 1 indeterminate for fusion. No significant change in segmental and overall cervical lordosis.

Introduction

Cervical spondylosis is a common cause of disability in individuals over the age of 50. Most occurrences of radicular symptoms due to cervical spondylosis and stenosis resolve spontaneously without surgery [1,2]. Recumbency, neck immobilization, and traction often provide relief of radiculopathy with minimal effect on anatomy [3-7] This suggests that only subtle anatomic changes are necessary to provide clinical relief. Patients with symptoms recalcitrant to conservative care are offered surgery. The most common surgical treatment for patients with unremitting radicular pain is anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF). In this procedure, complete discectomy and osteophyte removal are followed by insertion of either bone graft or prosthetic disc replacement [8,9]. Complications associated with anterior reconstruction as well as risk for adjacent segment degeneration and increased rates of subsequent surgery have been well-documented in the literature [10-12]. In select cases, posterior foraminotomy has been described as an alternative to anterior reconstruction but has limited adoption [13-16].

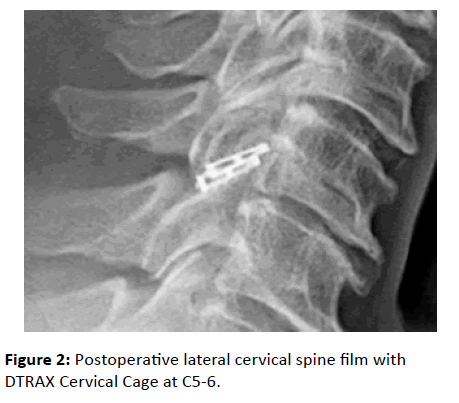

An alternative option to ACDF involves the placement of a titanium cervical cage between each facet joint at the symptomatic level using a posterior approach (DTRAX® Cervical Cage, Providence Medical Technology; Lafayette, CA) (Figure 1). Placement of the implants between the facet joints takes advantage of the inclination of the cervical facet in the transverse plane to indirectly open the neural foramina. The facets are immediately stabilized with instrumented distraction and decortication.

Figure 1 A 49-year old patient came for L4-L5 and L5-S1 discogenic disc diseases (A, B and C). A poor quality of the bone has been suspected intra-operatively. Then, a secondary displacement of the L4-L5 implant occurred at day 5 without any trauma (D). The implant has been retrieved and replaced by an interbody fusion (E). A posteriori, the bone metabolic balance found an osteopenia by hypovitaminosis D.

Herein we report clinical and radiographic outcomes of ten patients with radiculopathy due to cervical spondylosis and foraminal stenosis treated with single level posterior cervical fusion using bilateral cervical cages.

Material and Methods

The medical charts of 10 patients who underwent posterior cervical fusion using posterior cages treated by a single surgeon (BM) between 2013 and 2014 with minimum of 12 months of follow-up were reviewed. The following data were collected: Neck Disability Index (NDI) and neck and arm pain measured on Visual Analog Scale (VAS) administered at baseline and 6-weeks, 3-, 6- and 12-months post-operatively, X-ray and CT imaging pre-operatively and at 12 months postoperatively, and adverse events at all follow-up time points. Institutional review board approval was obtained before beginning the study.

All treated patients were diagnosed with cervical spondylosis and stenosis with radicular symptoms originating from a single spinal level. Diagnosis was made using a combination of clinical history, neurologic examination, advanced imaging, and in some cases, selective nerve block or electrical studies. All patients underwent a minimum of 6 weeks of conservative medical management prior to surgery. Medical management consisted of a combination of activity modification, cervical collar immobilization, epidural steroids, physical therapy, and chiropractic care.

Surgical recommendation was made for patients who had unilateral radicular pain, decreased reflexes or loss of strength and/or sensation, positive Spurling’s sign, preoperative Neck Disability Index (NDI) score greater than or equal to 30, and preoperative neck and arm pain score (VAS) greater than or equal to six. Contraindications to surgical management included motor strength antigravity or less in the symptomatic myotome, tobacco use, and metabolic bone disease.

Radiographic criteria for the procedure were cervical spondylosis from C3-C7 with advanced disc degeneration and loss of disc height (>33%). Radicular symptoms correlated with foraminal stenosis on MRI. Central stenosis was not a contraindication if the patient did not have spinal cord symptoms. Foraminal stenosis at other spinal levels was not a contraindication if asymptomatic. Patients with spondylolisthesis >3.5 mm or signs of instability on dynamic views were not offered posterior cervical fusion. Cervical kyphosis was an exclusion criterion but a neutral cervical spinal alignment was not.

All patients had preoperative MRI and standing cervical spine films with dynamic views. Cervical x-rays were obtained at six weeks, three months and one year. Segmental lordosis at the treated level and overall cervical lordosis (superior endplate of C3 to the superior endplate of C7) was measured using Cobb’s technique on standing lateral and flexionextension radiographs preoperatively and at one year postoperatively. Change in interspinous distance at the treated level on lateral flexion/extension radiographs was performed preoperatively and at one year. Fusion was defined as less than 2mm change in interspinous distance on flexion/ extension radiographs.

CT scans were obtained at 12-months postoperatively. Criteria for fusion was bridging trabecular bone of the posterior spine. Uncertain fusion on CT was defined as no halo around the implant but no clear bridging bone on reconstructions. Non-union was defined as absence of bridging bone, bone radiolucency, or implant migration.

At one-year follow-up, patients were assessed for neurologic symptoms and safety information which included the type, frequency, seriousness and relatedness of adverse events (AEs), and serious adverse events (SAEs). Neurologic and spinal examinations were performed.

Surgical technique

A fluoroscopically-guided posterior approach was used to place posterior cervical cages bilaterally between the facet joints of the target level according to the manufacturer’s surgical technique [17]. More specifically, following administration of general endotracheal anesthesia, the patient was turned prone with the face placed on a donut shaped support. Fluoroscopy was used to visualize the cervical spine and if necessary, the patient’s shoulders were pulled down with tape to optimize visualization. The neck and upper back were prepped in the normal sterile fashion. A cranial-caudal incision site was initiated under lateral fluoroscopy by lining up an externally placed (perpendicular to skin) Steinman pin with the intended facet. The actual incision was then made two to three levels below the treated level depending on facet anatomy. Incision was just lateral to mid-line, carried through the subcutaneous tissue, where the surgical site could be directly visualized. Paraspinal muscles were stripped from the spinous process and displaced laterally. An access chisel was inserted through the incision into the facet at the symptomatic level using fluoroscopic guidance. Fascia and muscle attachments were dissected off the lamina and facet using a rotating cutting instrument. A guide tube was then placed over the chisel to maintain facet distraction, provide visualization, and serve as a working channel. The guide tube has radiologic features to ensure proper implant positioning, including a radiolucent eye and a ridge that should proximate the posterior facet margin on lateral fluoroscopy when in place. The access chisel was then removed and facet articular surfaces were decorticated with rasps. A posterior cervical cage was packed with demineralized bone matrix and inserted into the facet to the pedicle (Figure 2). Additional bone graft material was inserted through the guide tube into the facet joint over the prepared bony surfaces. Paraspinal muscles and subcutaneous tissues were sequentially closed with sutures and a sterile dressing applied. The above procedure was then repeated on the contralateral side. Patients were fitted with a soft collar and instructed to wear the collar for six weeks.

Results

Mean subject age was 68 years (range 51-78), 6 were male and 4 were female (Table 1). Median duration of symptoms was four months (range 2-24 months). Five subjects were treated at C5-C6, four at C6-C7 and one at C4-C5.

| Mean Age | 68 years | |

| Age range | 51-78 years | |

| Gender | Male: 6 Female: 4 |

|

| Levels Treated | C4 – C5 | 1 |

| C5 – C6 | 5 | |

| C6 – C7 | 4 | |

| Duration of radicular symptoms | Range: 2 – 24 months Median: 4 months |

|

| Duration of bilateral radicular symptoms | 2 months | |

Table 1: Demographic data.

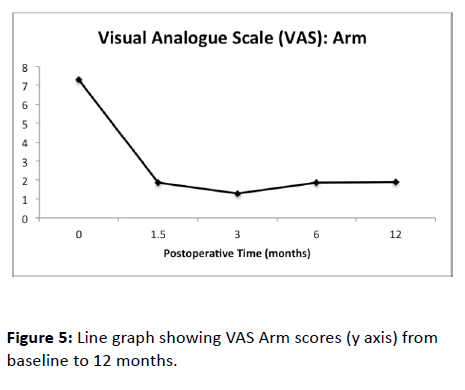

All patients had immediate and sustained improvement in NDI and VAS scores. NDI scores improved from a mean of 35 at baseline to 10, 12, 12 and 15 at 6-weeks, 3-, 6- and 12-months post-operatively, respectively (Figure 3). Neck pain on VAS improved from a mean of 8 pre-operatively to 2.5 at all followup time points (Figure 4). Arm pain on VAS improved from 7.5 at baseline to 1.5 at follow-up (Figure 5). There were no nerve root palsies, reoperations, or vertebral artery injuries. One patient had a stitch abscess that resolved after a course of antibiotics. At one year, there was no evidence of bone radiolucency, cage migration, or implant breakage.

Radiographic results showed minimal net change in overall cervical spine lordosis or Cobb’s angle at the treated level (-0.1, 0.4 net change, respectively) (Table 2). Definitive bridging bone was observed on CT scan at one year for 90% of subjects; it was indeterminate in one subject. However, no changes in interspinous distance were observed for this subject on lateral dynamic films and there was no evidence of cage migration (Figures 3-5).

| Measurement | Baseline | 12 + months | Net Change from Baseline at 12+ months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Cervical Spine Lordosis(degrees) | 8.6 ± 3.5 | 8.5 ± 3.4 | -0.1 |

| Cobbs angle at treated level (degrees) | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | +0.4 |

| Change in distance between adjacent spinous processes on lateral flexion and extension films (mm) | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | -2.9 |

Table 2: Summary of radiographic data.

Discussion

The study presents favorable one-year clinical and radiographic outcomes in patients with single-level cervical radiculopathy treated with minimally disruptive cervical fusion using bilateral posterior cages. Implants used to distract and immobilize the cervical facets can successfully treat patients with spondylosis and stenosis with neurologic symptoms. This technique is intended to be more tissue sparing than a traditional open posterior approach and has potentially fewer comorbidities than anterior fusion. Access to the anterior spine remains open for future reconstructive surgery, if necessary, without the need to address scar tissue and anterior hardware. Furthermore, this approach provides indirect neural decompression without the need for directly decompressing the involved nerve root. This concept has been supported by a cadaveric study, in which Tan et al. demonstrated an average increase in foraminal area of 18.4% after placement of an intra-facet spacer [18].

An open posterior approach to the cervical facets and placement of implants for distraction and indirect neuroforaminal decompression was described for the treatment of radiculopathy and myelopathy by Goel and Shah. 6 In their retrospective analysis, the authors reported excellent results in 25 patients (70%) with 6-month minimum follow-up. McCormack et al. reported good clinical results in 60 patients with single-level radiculopathy due to cervical stenosis and spondylosis treated with a minimally disruptive facet fusion approach using an expandable posterior cervical cage at one year [19].

Favourable outcomes in this small cohort may not be extrapolated to all patients with spinal stenosis and radiculopathy. Patients were carefully selected and those with risk factors for incomplete bone healing were excluded. The majority of patients in the present study had unilateral radiculopathy. Bilateral symptoms are more often associated with central canal stenosis that may require laminectomy or anterior approach. The use of posterior cages in this case series did not result in any significant changes in segmental and overall cervical lordosis at one year compared to baseline. Instrumented posterior distraction, however, at multiple levels could cause kyphosis because the implant is posterior to the instantaneous axis of rotation. Not all patients may be treated with posterior cervical fusion with facet distraction. Arthritic or partially fused facets may be difficult or impossible to access and body habitus may preclude visualization at C6-7 and C7-T1 to safely perform the procedure.

This study advances the notion that a subtle surgical adjustment of two vertebrae can alleviate radicular symptoms in patients with cervical spondylosis that are typically treated with a reconstructive procedure. Prospective studies are needed to make valid comparisons to existing surgical techniques.

Conclusions

One-year results demonstrate that minimally disruptive posterior cervical fusion using bilateral posterior cervical cages may provide symptom relief in select patients with cervical spondylotic radiculopathy. Further studies are needed to make valid comparisons to current techniques of anterior cervical fusion or foraminotomy.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2012 (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf10/p100012b.pdf) Accessed on: January 29, 2013.

- Christensen KD, Buswell K (2008) Chiropractic outcomes managing radiculopathy in a hospital setting: a retrospective review of 162 patients. J Chiropr Med 7: 115-125.

- Chung TS, Lee YJ, Kang SW, Park CJ, Kang WS, et al. (2002) Reducibility of cervical disk herniation: evaluation at MR imaging during cervical traction with a nonmagnetic traction device. Radiology 225: 895-900.

- Constantoyannis C,Konstantinou D, Kourtopoulos H, Papadakis N (2002) Intermittent cervical traction for cervical radiculopathy caused by large-volume herniated disks. J Manipulative PhysiolTher 25: 188-192.

- Jellad A, Ben Salah Z, Boudokhane S, Migaou H, Bahri I, et al. (2009) The value of intermittent cervical traction in recent cervical radiculopathy. Ann PhysRehabil Med 52: 638-652.

- Liu J,Ebraheim NA, Sanford CG Jr, Patil V, Elsamaloty H, et al. (2008) Quantitative changes in the cervical neural foramen resulting from axial traction: in vivo imaging study. Spine J 8: 619-623.

- Sari H, Akarirmak U, Karacan I, Akman H: Evaluation of Effects of Cervical Traction on Spinal Structures By Computerized Tomography. Adv Physiotherapy 5:114-12 2003

- Grochulla F(2012) Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion, in Vieweg U, Grochulla F (ed): Manual of Spine Surgery. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 201 pp 127-133

- Fountas KN,Kapsalaki EZ, Nikolakakos LG, Smisson HF, Johnston KW, et al. (2007) Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32: 2310-2317.

- Hilibrand AS, Robbins M (2004) Adjacent segment degeneration and adjacent segment disease: the consequences of spinal fusion? Spine J 4: 190S-194S.

- Riley LH 3rd,Vaccaro AR, Dettori JR, Hashimoto R (2010) Postoperative dysphagia in anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine 35: S76-85.

- Ruetten S,Komp M, Merk H, Godolias G (2008) Full-endoscopic cervical posterior foraminotomy for the operation of lateral disc herniations using 5.9-mm endoscopes: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Spine 33: 940-948.

- Tan LA, Gerard CS, Anderson PA, Traynelis VC (2014) Effect of machined interfacet allograft spacers on cervical foraminal height and area. J Neurosurg Spine 20: 178-182.

- McCormack BM,Bundoc RC, Ver MR, Ignacio JM, Berven SH, et al. (2013) Percutaneous posterior cervical fusion with the DTRAX Facet System for single-level radiculopathy: results in 60 patients. J Neurosurg Spine 18: 245-254.

- Goel A Shah A (2011) Facetal distraction as treatment for single- and multilevel cervical spondylotic radiculopathy and myelopathy: a preliminary report. J Neurosurg Spine 14: 689- 696.

- Hilibrand AS,Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, Jones PK, Bohlman HH (1999) Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81: 519-528.

- Panjabi MM,Oxland T, Takata K, Goel V, Duranceau J, et al. (1993) Articular facets of the human spine. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 18: 1298-1310.

- Seo M Choi D (2008) Adjacent segment disease after fusion for cervical spondylosis; myth or reality? Br J Neurosurg 22: 195 -199.

- Siemionow K, McCormack BM, Menchetti PPM (2015) Tissue sparing posterior cervical indirect decompression and fusion in foraminal stenosis. In: Cerv. Spine Minim. Invasive Open Surg. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, New York, NY, 135-148.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences